CICO - The Endless Debate by Roxana Soetebeer MHP PHC

CICO - The Endless Debate

What if I told you that calories both matter and don't matter? I call them Schrödinger's calories.

CICO, which stands for "Calories In, Calories Out," is a simple concept that suggests weight loss or gain depends solely on the balance between the calories you consume and the calories you burn. If you eat fewer calories than your body needs for daily activities and basic functions, you'll supposedly lose weight. Sounds easy, right?

A few weeks ago, I poked the hornet's nest by daring to say that "Eat less, move more" is bad advice for someone who wants to lose weight. That tweet got over 1.3 million views and too many replies to read.

I said: Eating less and moving more is a sure way to work up an appetite and is not a good weight loss strategy.

I said that the key to losing weight is to eat less and exercise more and this "metabolic health practitioner" finds that idea so absurd that she assumes it must be a joke. https://t.co/JP2catLx6p

— Matt Walsh (@MattWalshBlog) April 26, 2024

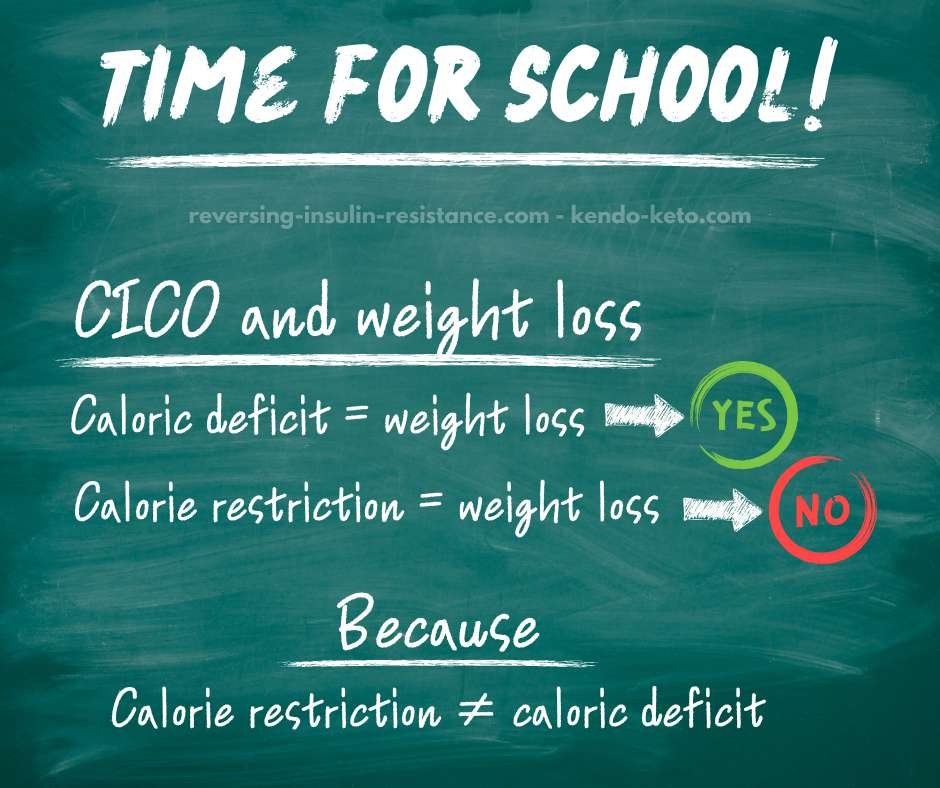

Many responded that my 100-pound weight loss was the result of calorie restriction, while others said I was in a caloric deficit.

Unfortunately, I added to the confusion by not making the distinction between calorie restriction and a caloric deficit. I want to clear that up now and hopefully avoid future debates. OK, I won't avoid them, but hopefully, people will start to get it.

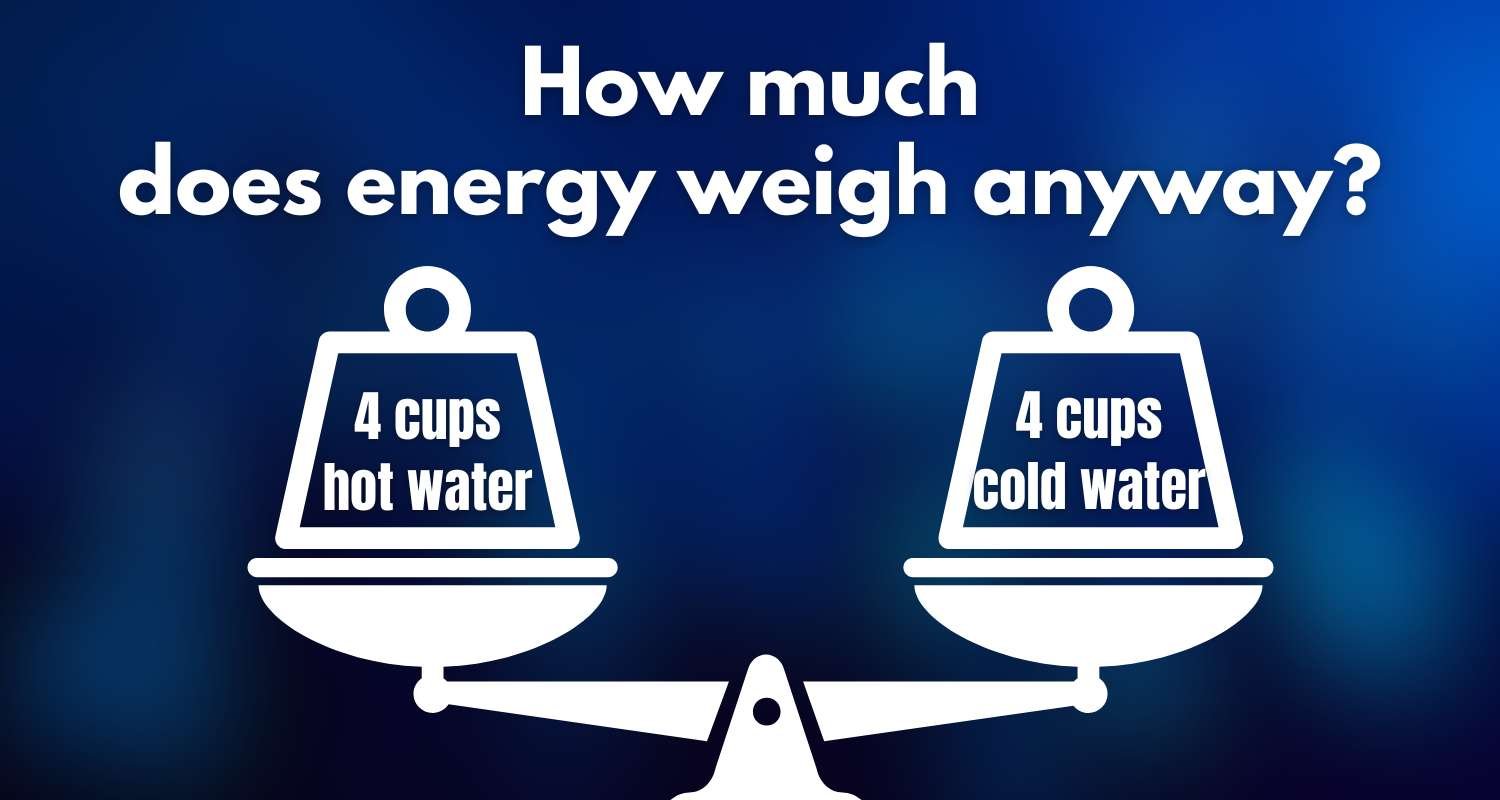

First off, we are not eating calories. Thanks, Prof. Bart Kay, for teaching me that. Our bodies are not bomb calorimeters; we don't burn calories.

Second, I didn't break the law of thermodynamics by losing weight without restricting calories. I want to think of myself as special, but I cannot break the laws of physics.

"Two fundamental concepts govern energy as it relates to living organisms: the First Law of Thermodynamics states that total energy in a closed system is neither lost nor gained — it is only transformed."

Are humans a closed system? Nope. We breathe, we sweat, and our bodies regulate temperature to adapt to our surroundings. We eat, we eliminate, we grow, and we shrink. Hormones regulate how fuel is partitioned. Not a closed system.

Back to what really matters: how do we lose weight? Why doesn't calorie restriction work, but a caloric deficit does?

A caloric deficit is usually observed after the fact. Someone lost weight, so that someone was in a caloric deficit. Seems simple enough.

To think that calorie restriction results in a caloric deficit is, unfortunately, too big of a leap or magical thinking.

Imagine an avid dieter. A quick Google search tells her that she needs about 2000 calories to maintain her weight (based on age and gender). To lose weight, she decides to restrict her daily intake of calories to 1000. That should put her in a caloric deficit of 1000 calories (spoiler: it doesn't). She calculates that she should lose two pounds per week since 2 pounds of fat store 7000 calories. So, in 6 months, she should lose 52 pounds.

Calories in are guesswork at best.

Calories on nutrition labels can be wildly inaccurate. They can legally be off by 20% according to the FDA Guidance for Industry: Guide for Developing and Using Data Bases for Nutrition Labeling. Despite all the diligent weighing and tracking, 1000 calories can become 1200. Whole foods vary in fat, protein, and carb content. A ribeye can be a little more or less fatty, messing up the calorie content by a lot.

Calories burned are mostly beyond our control, even with exercise. Yes, we can hit the gym. We can run on the treadmill to the tune of 360 calories. But unfortunately, our avid dieter can't run. Walking will get her 150 calories. But she isn't sure about her pace. More guesswork.

A week into her diet, she starts feeling cold and irritable. She is always hungry and has a hard time focusing on her tasks. What happened? Her body noticed the drop in calories. Well, not exactly; the body doesn't measure calories, but she ate a lot less food. So, to compensate, the body down-regulates less important processes like temperature and sends hunger signals to demand more food.

The next 5 months and 3 weeks are going to be hard. Will our dieter get used to feeling hungry? Will she be able to ignore feeling cold and miserable?

This is why most diets fail. These signals are hard to ignore. Willpower can overcome them for a while, but not for long. That's why the failure rate of long-term weight loss is so high.

The fact that our dieter is obese is a telltale sign that she is hyperinsulinemic. This means her body easily stores fat but doesn't let go of it easily. She cannot understand why her normal-weight sister maintains her body weight eating the very same food (before her diet adventure) while our dieter gained weight. We know that insulin resistance explains all that, but on the surface, it makes no sense and seems unfair.

Back to the topic. It is not easy to create a caloric deficit because the body won't play along. We are built for survival. The calculation is silly.

While the dieter restricts calories, the body counteracts by throttling the caloric demand (which makes her feel poorly), possibly down to only needing 1000 calories to meet basic needs. And the cleverly conceived restriction results in a zero caloric deficit. Oops, too bad.

After 4 weeks, our dieter gives up. She constantly obsesses about food and can no longer handle being cold and hungry. Who can blame her? Well, it turns out many people do. They tell her she is lazy, a slob, and lacks character and self-discipline. Some might even call her ugly, as I experienced. It doesn't bother me anymore, but our dieter is heartbroken and loses hope. She tried everything and failed. She won't try again.

What she didn't try is keto. A simple change in macros. Instead of counting calories, she could have counted carbs and prioritized protein and fat. A change that does not require calorie restriction or willpower, because keto provides satiety. Cravings are much easier to handle when hunger isn't a problem. Obsessing about food becomes a non-issue.

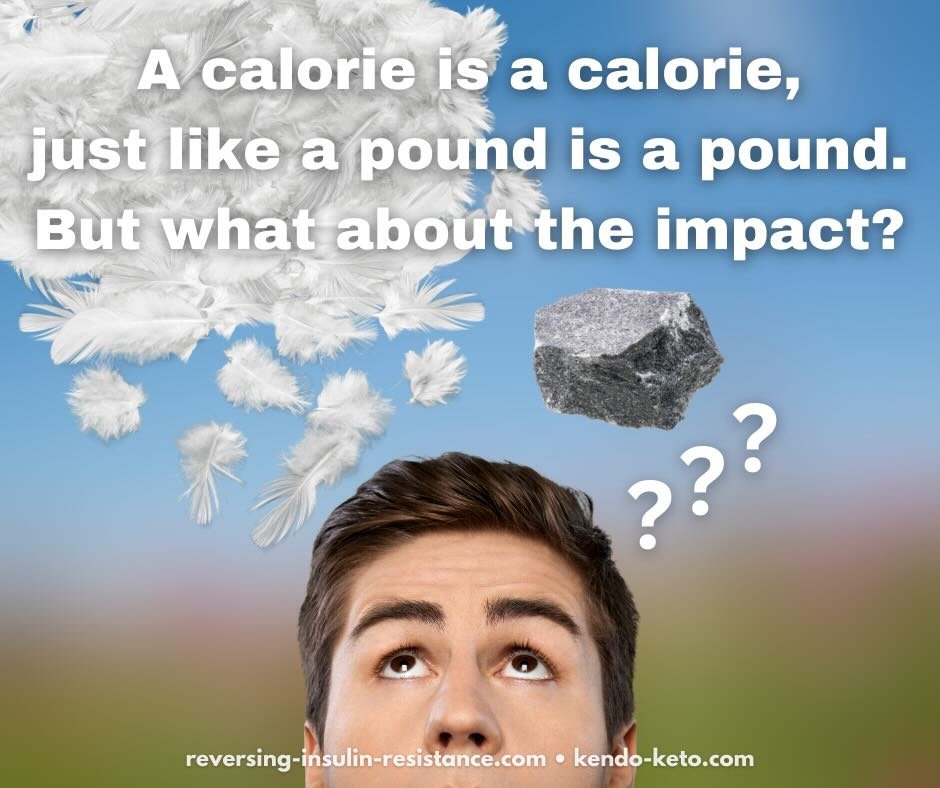

I lost 120 pounds. In hindsight, I know I was in a caloric deficit. But I never restricted calories. Not accidentally, not intentionally. The calories I ate were handled by my body in a very different way. When people say "a calorie is a calorie" they are right. A calorie is a unit to measure heat energy. But "a calorie is a calorie" is incorrect when it comes to the impact that calories from different foods have. Sugar—and I would argue that sugar is not a food—has a completely different impact than fat and protein, calorie per calorie. 500 calories worth of doughnuts and 500 calories worth of steak are metabolized in completely different ways. And to add to this, 500 calories worth of any food eaten by a healthy person and by a person with diabetes are also metabolized in different ways.

Does one pound of feathers hit the same as one pound rock?

"Eat less, move more" is terrible weight loss advice. Instead, count carbs, not calories.

Final thought: Exercise is wildly beneficial, but also a terrible weight loss tool. I will leave that discussion for another blog.

Written by Roxana Soetebeer, MHP, PHC

Published June 1st, 2024

Social Media:

Facebook

X Roxana

X Joy

Coaching: Are you stuck on your weight loss journey? Check out our coaching programs. Book a free discovery call to find out if we are a good fit.